The Git Object Model

The SHA

All the information needed to represent the history of a project is stored in files referenced by a 40-digit "object name" that looks something like this:

6ff87c4664981e4397625791c8ea3bbb5f2279a3

You will see these 40-character strings all over the place in Git. In each case the name is calculated by taking the SHA1 hash of the contents of the object. The SHA1 hash is a cryptographic hash function. What that means to us is that it is virtually impossible to find two different objects with the same name. This has a number of advantages; among others:

- Git can quickly determine whether two objects are identical or not, just by comparing names.

- Since object names are computed the same way in every repository, the same content stored in two repositories will always be stored under the same name.

- Git can detect errors when it reads an object, by checking that the object's name is still the SHA1 hash of its contents.

The Objects

Every object consists of three things - a type, a size and content. The size is simply the size of the contents, the contents depend on what type of object it is, and there are four different types of objects: "blob", "tree", "commit", and "tag".

- A "blob" is used to store file data - it is generally a file.

- A "tree" is basically like a directory - it references a bunch of other trees and/or blobs (i.e. files and sub-directories)

- A "commit" points to a single tree, marking it as what the project looked like at a certain point in time. It contains meta-information about that point in time, such as a timestamp, the author of the changes since the last commit, a pointer to the previous commit(s), etc.

- A "tag" is a way to mark a specific commit as special in some way. It is normally used to tag certain commits as specific releases or something along those lines.

Almost all of Git is built around manipulating this simple structure of four different object types. It is sort of its own little filesystem that sits on top of your machine's filesystem.

Different from SVN

It is important to note that this is very different from most SCM systems that you may be familiar with. Subversion, CVS, Perforce, Mercurial and the like all use Delta Storage systems - they store the differences between one commit and the next. Git does not do this - it stores a snapshot of what all the files in your project look like in this tree structure each time you commit. This is a very important concept to understand when using Git.

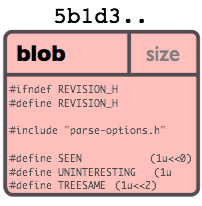

Blob Object

A blob generally stores the contents of a file.

You can use git show to examine the contents of any blob. Assuming we have the SHA for a blob, we can examine its contents like this:

$ git show 6ff87c4664

Note that the only valid version of the GPL as far as this project

is concerned is _this_ particular version of the license (ie v2, not

v2.2 or v3.x or whatever), unless explicitly otherwise stated.

...

A "blob" object is nothing but a chunk of binary data. It doesn't refer to anything else or have attributes of any kind, not even a file name.

Since the blob is entirely defined by its data, if two files in a directory tree (or in multiple different versions of the repository) have the same contents, they will share the same blob object. The object is totally independent of its location in the directory tree, and renaming a file does not change the object that file is associated with.

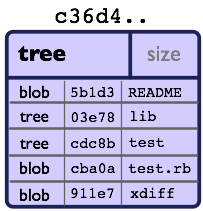

Tree Object

A tree is a simple object that has a bunch of pointers to blobs and other trees - it generally represents the contents of a directory or subdirectory.

The ever-versatile git show command can also be used to examine tree objects, but git ls-tree will give you more details. Assuming we have the SHA for a tree, we can examine it like this:

$ git ls-tree fb3a8bdd0ce

100644 blob 63c918c667fa005ff12ad89437f2fdc80926e21c .gitignore

100644 blob 5529b198e8d14decbe4ad99db3f7fb632de0439d .mailmap

100644 blob 6ff87c4664981e4397625791c8ea3bbb5f2279a3 COPYING

040000 tree 2fb783e477100ce076f6bf57e4a6f026013dc745 Documentation

100755 blob 3c0032cec592a765692234f1cba47dfdcc3a9200 GIT-VERSION-GEN

100644 blob 289b046a443c0647624607d471289b2c7dcd470b INSTALL

100644 blob 4eb463797adc693dc168b926b6932ff53f17d0b1 Makefile

100644 blob 548142c327a6790ff8821d67c2ee1eff7a656b52 README

...

As you can see, a tree object contains a list of entries, each with a mode, object type, SHA1 name, and name, sorted by name. It represents the contents of a single directory tree.

An object referenced by a tree may be blob, representing the contents of a file, or another tree, representing the contents of a subdirectory. Since trees and blobs, like all other objects, are named by the SHA1 hash of their contents, two trees have the same SHA1 name if and only if their contents (including, recursively, the contents of all subdirectories) are identical. This allows git to quickly determine the differences between two related tree objects, since it can ignore any entries with identical object names.

(Note: in the presence of submodules, trees may also have commits as entries. See the Submodules section.)

Note that the files all have mode 644 or 755: git actually only pays attention to the executable bit.

Commit Object

The "commit" object links a physical state of a tree with a description of how we got there and why.

You can use the --pretty=raw option to git show or git log to examine your favorite commit:

$ git show -s --pretty=raw 2be7fcb476

commit 2be7fcb4764f2dbcee52635b91fedb1b3dcf7ab4

tree fb3a8bdd0ceddd019615af4d57a53f43d8cee2bf

parent 257a84d9d02e90447b149af58b271c19405edb6a

author Dave Watson <dwatson@mimvista.com> 1187576872 -0400

committer Junio C Hamano <gitster@pobox.com> 1187591163 -0700

Fix misspelling of 'suppress' in docs

Signed-off-by: Junio C Hamano <gitster@pobox.com>

As you can see, a commit is defined by:

- a tree: The SHA1 name of a tree object (as defined below), representing the contents of a directory at a certain point in time.

- parent(s): The SHA1 name of some number of commits which represent the immediately previous step(s) in the history of the project. The example above has one parent; merge commits may have more than one. A commit with no parents is called a "root" commit, and represents the initial revision of a project. Each project must have at least one root. A project can also have multiple roots, though that isn't common (or necessarily a good idea).

- an author: The name of the person responsible for this change, together with its date.

- a committer: The name of the person who actually created the commit, with the date it was done. This may be different from the author; for example, if the author wrote a patch and emailed it to another person who used the patch to create the commit.

- a comment describing this commit.

Note that a commit does not itself contain any information about what actually changed; all changes are calculated by comparing the contents of the tree referred to by this commit with the trees associated with its parents. In particular, git does not attempt to record file renames explicitly, though it can identify cases where the existence of the same file data at changing paths suggests a rename. (See, for example, the -M option to git diff).

A commit is usually created by git commit, which creates a commit whose parent is normally the current HEAD, and whose tree is taken from the content currently stored in the index.

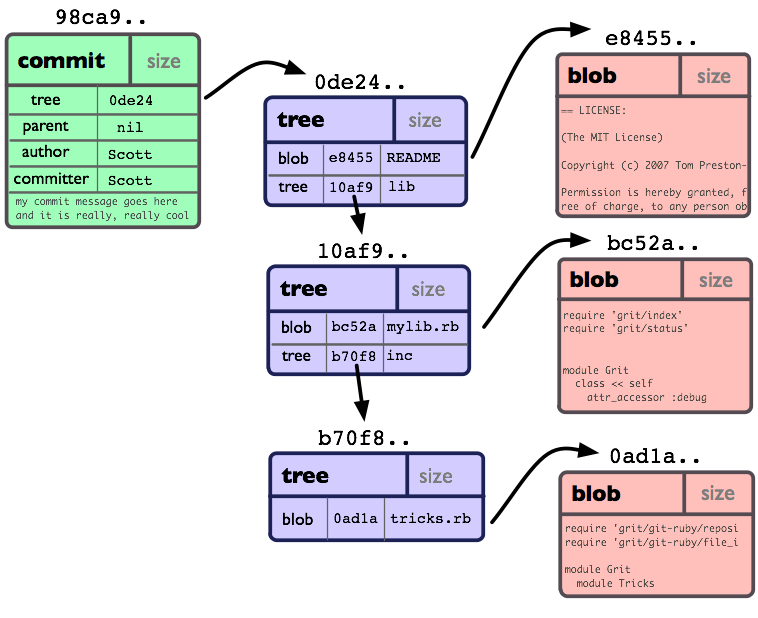

The Object Model

So, now that we've looked at the 3 main object types (blob, tree and commit), let's take a quick look at how they all fit together.

If we had a simple project with the following directory structure:

$>tree

.

|-- README

`-- lib

|-- inc

| `-- tricks.rb

`-- mylib.rb

2 directories, 3 files

And we committed this to a Git repository, it would be represented like this:

You can see that we have created a tree object for each directory (including the root) and a blob object for each file. Then we have a commit object to point to the root, so we can track what our project looked like when it was committed.

Tag Object

A tag object contains an object name (called simply 'object'), object type, tag name, the name of the person ("tagger") who created the tag, and a message, which may contain a signature, as can be seen using git cat-file:

$ git cat-file tag v1.5.0

object 437b1b20df4b356c9342dac8d38849f24ef44f27

type commit

tag v1.5.0

tagger Junio C Hamano <junkio@cox.net> 1171411200 +0000

GIT 1.5.0

-----BEGIN PGP SIGNATURE-----

Version: GnuPG v1.4.6 (GNU/Linux)

iD8DBQBF0lGqwMbZpPMRm5oRAuRiAJ9ohBLd7s2kqjkKlq1qqC57SbnmzQCdG4ui

nLE/L9aUXdWeTFPron96DLA=

=2E+0

-----END PGP SIGNATURE-----

See the git tag command to learn how to create and verify tag objects. (Note that git tag can also be used to create "lightweight tags", which are not tag objects at all, but just simple references whose names begin with "refs/tags/").